|

|

October 3rd, 2016

Ever wondered what caused a particular bulge or marking on a case? And more importantly, does the issue make the case unsafe for further use? Sierra Bullets Ballistic Technician Duane Siercks offers some insight into various issues and their causes in this article from the Sierra Blog.

Diagnosing Problems with Cartridge Brass

by Duane Siercks, Sierra Bullets

I was handed a small sample of .223 Rem cases the other day and was asked if I could comment on some marks and appearances that had been noticed as they were sorting through the cases. I will share what was observed and give you what would seem to be a cause for them. These were from an unknown source, so I have no way of knowing what type of firearm they were fired in or if they were factory loaded or reloaded ammunition.

Example ONE: Lake City 5.56, Unknown Year

Case #1 was seen to have a very rounded shoulder and split. Upon first look it was obvious that this round had been a victim of excess pressure. The firearm (perhaps an AR?) was apparently not in full battery, or there was possibly a headspace issue also. While taking a closer look, the primer was very flat and the outside radius of the primer cup had been lost. High pressure! Then I also noticed that there was an ejector mark on the case rim. This is most certainly an incident of excessive pressure. This case is ruined and should be discarded. See photo below.

Example TWO: Lake City Match 1993

Case #2 appears very normal. There was some question about marks seen on the primer. The primer is not overly flattened and is typical for a safe maximum load. There is a small amount of cratering seen here. This can be caused by a couple of situations.

Cratering is often referred to as a sign of excess pressure. With safety in mind, this is probably something that should make one stop and really assess the situation. Being as there are no other signs of pressure seen with this case, I doubt that pressure was unsafe. That leads us to the next possibility. This can also be caused by the firing-pin hole in the bolt-face being a bit larger than the firing-pin, and allowing the primer to flow back into the firing-pin hole causing the crater seen here. This can happen even with less-than-max pressures, in fact it has been noted even at starting loads. Always question whether pressure is involved when you see a crater. In this situation, I lean toward a large firing-pin hole. This case should be safe to reload.

Example THREE: R-P .223 Remington

Case #3 appears normal with one exception. There are two rings seen about one half inch below the base of the shoulder. These rings are around the circumference of the case, one being quite pronounced, and the other being noticeably less.

As we do not know the origin of the firearm in which this case was fired, it does seem apparent that the chamber of the firearm possibly had a slight defect. It could have been that the reamer was damaged during the cutting of this chamber. I would suggest that the chamber did have a couple of grooves that imprinted onto the case upon firing. This firearm, while maybe not dangerous should be looked at by a competent gunsmith. In all likelihood, this case is still safe to use.

Example FOUR: R-P .223 Remington

Case #4 has no signs of excess pressure. There is a bulge in the case just ahead of the case head that some might be alarmed by. This bulge is more than likely caused by this case being fired in a firearm that had a chamber on the maximum side of S.A.A.M.I. specifications. There is actually no real issue with the case. Note that the primer would indicate this load was relatively mild on pressure.

If this case was reloaded and used in the same firearm numerous times there might be a concern about case head separation. If you were going to use this case to load in an AR, be sure to completely full-length re-size to avoid chambering difficulties. This case would be safe to reload.

It is very important to observe and inspect your cases before each reloading. After awhile it becomes second nature to notice the little things. Never get complacent as you become more familiar with the reloading process. If ever in doubt, call Sierra’s Techs at 1-800-223-8799.

August 24th, 2016

In this .308 Win test, 70° F ammo shot 96 FPS slower than ammo heated to 130.5° F. And the 130.5° ammo was 145 fps faster than ammo right out of the freezer (at 25.5° F). That’s a huge difference…

EDITOR’s NOTE: The Sierra tester does not reveal the brand of powder tested here. Some powders are much more temp sensitive than others. Accordingly, you cannot extrapolate test results from one propellant to another. Nonetheless, it is interesting to see the actual recorded velocity shift with ammo temperature variations in a .308 Win.

Written by Sierra Chief Ballistician Tommy Todd

This story originally appeared in the Sierra Bullets Blog

A few weeks ago I was attending the Missouri State F-Class Match. This was a two-day event during the summer and temperatures were hot one day and hotter the next. I shot next to a gentleman who was relatively new to the sport. He was shooting a basically factory rifle and was enjoying himself with the exception that his scores were not as good as he hoped they would be and he was experiencing pressure issues with his ammunition. I noticed that he was having to force the bolt open on a couple of rounds. During a break, I visited with him and offered a couple of suggestions which helped his situation somewhat and he was able to finish the match without major issues.

He was shooting factory ammunition, which is normally loaded to upper levels of allowable pressures. While this ammunition showed no problems during “normal” testing, it was definitely showing issues during a 20-round string of fire in the temperatures we were competing in. My first suggestion was that he keep his ammunition out of the direct sun and shade it as much as possible. My second suggestion was to not close the bolt on a cartridge until he was ready to fire. He had his ammo in the direct sunlight and was chambering a round while waiting on the target to be pulled and scored which can take from a few seconds to almost a minute sometimes.

This time frame allowed the bullet and powder to absorb chamber [heat] and build pressure/velocity above normal conditions. Making my recommended changes lowered the pressures enough for the rifle and cartridge to function normally.

Testing Effects of Ammunition Temperature on Velocity and POI

After thinking about this situation, I decided to perform a test in the Sierra Bullets underground range to see what temperature changes will do to a rifle/cartridge combination. I acquired thirty consecutive .30 caliber 175 grain MatchKing bullets #2275 right off one of our bullet assembly presses and loaded them into .308 Winchester ammunition. I utilized an unnamed powder manufacturer’s product that is appropriate for the .308 Winchester cartridge. This load is not at the maximum for this cartridge, but it gives consistent velocities and accuracy for testing.

I took ten of the cartridges and placed them in a freezer to condition.

I set ten of them on my loading bench, and since it was cool and cloudy the day I performed this test I utilized a floodlight and stand to simulate ammunition being heated in the sun.

I kept track of the temperatures of the three ammunition samples with a non-contact laser thermometer.

The rifle was fired at room temperature (70 degrees) with all three sets of ammunition. I fired this test at 200 yards out of a return-to-battery machine rest. The aiming point was a leveled line drawn on a sheet of paper. I fired one group with the scope aimed at the line and then moved the aiming point across the paper from left to right for the subsequent groups.

NOTE that the velocity increased as the temperature of the ammunition did.

The ammunition from the freezer shot at 2451 fps.

The room temperature ammunition shot at 2500 fps.

The heated ammunition shot at 2596 fps.

The tune window of the particular rifle is fairly wide as is shown by the accuracy of the three pressure/velocity levels and good accuracy was achieved across the board. However, notice the point of impact shift with the third group? There is enough shift at 200 yards to cause a miss if you were shooting a target or animal at longer ranges. While the pressure and velocities changed this load was far enough from maximum that perceived over pressure issues such as flattened primer, ejector marks on the case head, or sticky extraction did not appear. If you load to maximum and then subject your ammunition to this test your results will probably be magnified in comparison.

This test showed that pressures, velocities, and point-of-impact can be affected by temperatures of your ammunition at the time of firing. It’s really not a bad idea to test in the conditions that you plan on utilizing the ammo/firearm in if at all possible. It wouldn’t be a bad idea to also test to see what condition changes do to your particular gun and ammunition combination so that you can make allowances as needed. Any personal testing along these lines should be done with caution as some powder and cartridge combination could become unsafe with relatively small changes in conditions.

July 1st, 2016

Well folks, it’s July 1st already — the means we’re moving into “peak heat” summer conditions. It’s vitally important to keep your ammo at “normal” temps during the hot summer months. Even if you use “temp-insensitive” powders, studies suggest that pressures can still rise dramatically when the entire cartridge gets hot, possibly because of primer heating. It’s smart to keep your loaded ammo in an insulated storage unit, possibly with a Blue Ice Cool Pak if you expect it to get quite hot. Don’t leave your ammo in the car or truck — temps can exceed 140° in a vehicle parked in the sun.

To learn more about how ambient temperature (and primer choice) affect pressures (and hence velocities) you should read the article Pressure Factors: How Temperature, Powder, and Primer Affect Pressure by Denton Bramwell. In that article, the author uses a pressure trace instrument to analyze how temperature affects ammo performance. Bramwell’s tests yielded some fascinating results. To learn more about how ambient temperature (and primer choice) affect pressures (and hence velocities) you should read the article Pressure Factors: How Temperature, Powder, and Primer Affect Pressure by Denton Bramwell. In that article, the author uses a pressure trace instrument to analyze how temperature affects ammo performance. Bramwell’s tests yielded some fascinating results.

For example, barrel temperature was a key factor: “Both barrel temperature and powder temperature are important variables, and they are not the same variable. If you fail to take barrel temperature into account while doing pressure testing, your test results will be very significantly affected. The effect of barrel temperature is around 204 PSI per F° for the Varget load. If you’re not controlling barrel temperature, you about as well might not bother controlling powder temperature, either. In the cases investigated, barrel temperature is a much stronger variable than powder temperature.” |

Powder Heat Sensitivity Comparison Test

Our friend Cal Zant of the Precision Rifle Blog recently published a fascinating comparison test of four powders: Hodgdon H4350, Hodgdon Varget, IMR 4451, and IMR 4166. The first two are Hodgdon Extreme powders, while the latter two are part of IMR’s new Enduron line of propellants.

CLICK HERE to VIEW FULL TEST RESULTS

The testers measured the velocity of the powders over a wide temperature range, from 25° F to 140° F. Hodgdon H4350 proved to be the most temp stable of the four powders tested.

December 16th, 2015

It may seem obvious, but you need to be careful when changing primer types for a pet load. Testing with a .308 Win rifle and Varget powder has confirmed that a primer change alone can result in noteworthy changes in muzzle velocity. To get more MV, you’ll need a more energy at some point in the process — and that potentially means more pressure. So exercise caution when changing primer types

We are often asked “Can I get more velocity by switching primer types?” The answer is “maybe”. The important thing to know is that changing primer types can alter your load’s performance in many ways — velocity average, velocity variance (ES/SD), accuracy, and pressure. Because there are so many variables involved you can’t really predict whether one primer type is going to be better or worse than another. This will depend on your cartridge, your powder, your barrel, and even the mechanics of your firing pin system.

Interestingly, however, a shooter on another forum did a test with his .308 Win semi-auto. Using Hodgdon Varget powder and Sierra 155gr Palma MatchKing (item 2156) bullets, he found that Wolf Large Rifle primers gave slightly higher velocities than did CCI-BR2s. Interestingly, the amount of extra speed (provided by the Wolfs) increased as charge weight went up, though the middle value had the largest speed variance. The shooter observed: “The Wolf primers seemed to be obviously hotter and they had about the same or possibly better ES average.” See table:

| Varget .308 load |

45.5 grains |

46.0 grains |

46.5 grains |

| CCI BR2 Primers |

2751 fps |

2761 fps |

2783 fps |

| Wolf LR Primers |

2757 fps |

2780 fps |

2798 fps |

| Speed Delta |

6 fps |

19 fps |

15 fps |

You can’t extrapolate too much from the table above. This describes just one gun, one powder, and one bullet. Your Mileage May Vary (YMMV) as they say. However, this illustration does show that by substituting one component you may see significant changes. Provided it can be repeated in multiple chrono runs, an increase of 19 fps (with the 46.0 grain powder load) is meaningful. An extra 20 fps or so may yield a more optimal accuracy node or “sweet spot” that produces better groups. (Though faster is certainly NOT always better for accuracy — you have to test to find out.)

WARNING: When switching primers, you should exercise caution. More speed may be attractive, but you have to consider that the “speedier” primer choice may also produce more pressure. Therefore, you must carefully monitor pressure signs whenever changing ANY component in a load.

October 13th, 2014

by Philip Mahin, Sierra Bullets Ballistic Technician

This article first appeared in the Sierra Bullets Blog

The ANSI / SAAMI group, short for “American National Standard Institute” and “Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute”, have made available some time back the voluntary industry performance standards for pressure and velocity of centerfire rifle sporting ammunition for the use of commercial manufacturers. [These standards for] individual cartridges [include] the velocity on the basis of the nominal mean velocity from each, the maximum average pressure (MAP) for each, and cartridge and chamber drawings with dimensions included. The cartridge drawings can be seen by searching the internet and using the phrase ‘308 SAAMI’ will get you the .308 Winchester in PDF form. What I really wanted to discuss today was the differences between the two accepted methods of obtaining pressure listings. The Pounds per Square Inch (PSI) and the older Copper Units of Pressure (CUP) version can both be found in the PDF pamphlet.

Image by ModernArms, Creative Common License.

CUP Pressure Measurement CUP Pressure Measurement

The CUP system uses a copper crush cylinder which is compressed by a piston fitted to a piston hole into the chamber of the test barrel. Pressure generated by the burning propellant causes the piston to move and compress the copper cylinder. This will give it a specific measurable size that can be compared to a set standard. At right is a photo of a case that was used in this method and you can see the ring left by the piston hole.

PSI Pressure Measurement

What the book lists as the preferred method is the PSI (pounds per square inch or, more accurately, pound-force per square inch) version using a piezoelectric transducer system with the transducer flush mounted in the chamber of the test barrel. Pressure developed by the burning propellant pushes on the transducer through the case wall causing it to deflect and make a measurable electric charge.

Q: Is there a standardized correlation or mathematical conversion ratio between CUP and PSI values?

Mahin: As far as I can tell (and anyone else can tell me) … there is no [standard conversion ratio or] correlation between them. An example of this is the .223 Remington cartridge that lists a MAP of 52,000 CUP / 55,000 PSI but a .308 Winchester lists a 52,000 CUP / 62,000 PSI and a 30-30 lists a 38,000 CUP / 42,000 PSI. It leaves me scratching my head also but it is what it is. The two different methods will show up in listed powder data[.]

So the question on most of your minds is what does my favorite pet load give for pressure? The truth is the only way to know for sure is to get the specialized equipment and test your own components but this is going to be way out of reach for the average shooter, myself included. The reality is that as long as you are using printed data and working up from a safe start load within it, you should be under the listed MAP and have no reason for concern. Being specific in your components and going to the load data representing the bullet from a specific cartridge will help get you safe accuracy. [With a .308 Winchester] if you are to use the 1% rule and work up [from a starting load] in 0.4 grain increments, you should be able to find an accuracy load that will suit your needs without seeing pressure signs doing it. This is a key to component longevity and is the same thing we advise [via our customer service lines] every day. Till next time, be safe and enjoy your shooting.

October 7th, 2014

The digital archives of Shooting Sports USA feature an interview with Olympic smallbore shooter Lones Wigger. This constitutes the third and final part in a series by Jock Elliott on pressure during a match and the methods top shooters use to handle their nerves. Read Part I | Read Part II.

The Fine Art of Not Cracking Under Pressure – Part III

by Lones Wigger, Smallbore Rifle Olympic Medalist

It’s pretty complicated — this subject of dealing with pressure. I’m a precision shooter and have learned to excel in that discipline. You’ve got to learn to shoot the desired scores at home and in training. And once you’re capable of shooting the scores, you may not shoot the same way in the match because of the match pressure. As a result, it takes 3-4 years to learn how to shoot, and another 3-4 years to learn how to win — to deal with the match pressure. It takes several more years to learn how to do it when it counts. It’s pretty complicated — this subject of dealing with pressure. I’m a precision shooter and have learned to excel in that discipline. You’ve got to learn to shoot the desired scores at home and in training. And once you’re capable of shooting the scores, you may not shoot the same way in the match because of the match pressure. As a result, it takes 3-4 years to learn how to shoot, and another 3-4 years to learn how to win — to deal with the match pressure. It takes several more years to learn how to do it when it counts.

To win, there are several things you have to learn how to do. You have to do it from within. You have to learn how to train just as if you were in a big competition. You work on every shot. You have got to learn to treat it just like a match — to get the maximum value out of every shot. You have got to use the same technique in practice and in training. A lot of shooters have a problem because they change their technique from practice to the match. In competition, you work your ass off for every shot. You have to approach the training the same way.

A second way to combat pressure is to shoot in every competition you can get into so that you become accustomed to it.

Do Everything Possible to Prepare

The third technique is preparation. Before you are going to shoot in a big competition, train hard to do everything you can to raise your scores. So when you’re in the match, you know that you have done everything humanly possible to get ready for the competition. If you have self-doubt, you will not shoot well. You have to have the will to prepare to win.

When Gary Anderson was a kid, he couldn’t afford a gun or ammunition. He had read about the great Soviet shooters. With his single shot rifle, he would get into position, point that gun and dry fi re for hours at a time in the three different positions. He had tremendous desire. He wanted to win and he did whatever he could to get there. When he finally got into competition, he shot fantastic scores from the beginning.

Visualize Winning to Train the Subconscious Mind

A little bit of psychology: You picture in your mind what you want to do. You have to say, OK, I’m going to the Olympics and perform well. Picture yourself shooting a great score and how good it feels. You are training your subconscious mind. Once you get it trained, it takes over. A coach taught me to visualize the outcome, and it worked. Eventually you train your subconscious and it believes you can win. At first I didn’t know about teaching the subconscious to take over, but now I do it all the time. And it certainly worked for me at the 1972 Olympics. What it really takes is training and doing the same thing in training as at a match. If you are “just shooting,” you are wasting your time. READ MORE….

CLICK HERE to READ FULL ARTICLE featuring interviews with Brian Zins, Bruce Piatt, Carl Bernosky and Ernie Vande Zande. (Article take some time to load.)

Story courtesy The NRA Blog and Shooting Sports USA.

April 1st, 2014

Ever wonder why fine wine is always stored on its side? That’s not just for looks, or easier access when the sommelier (wine steward) visits the wine cellar. Wine bottles are stored horizontally, at a slight angle, to prevent the wine from oxidizing:

“By intentionally storing a wine on its side, you will help keep the cork in constant contact with the wine. This will keep the cork moist, which should keep the cork from shrinking and allowing the enemy of wine, oxygen, to seep into the bottle. When oxygen comes into contact with wine the result is not good – the wine starts to oxidize and the aromas, flavors and color all begin to spoil“. — About.com

Ammunition Should Also Be Stored Horizontally

So what does wine have to do with shooting? Well, it may surprise you, but over time, our cartridges can spoil, just like wine can — though not for the same reason. We don’t have the issue of oxygen seeping past the bullet (the “cork” as it were). However, when ammunition is stored nose-up or nose down, problems can arise. In a nose-up or nose-down configuration, over a long period of time, the powder column will compress, and the powder kernels can actually break down. This can lead to erratic ignition and/or dangerous pressures.

To avoid the problems associated with powder column compression and kernel break-down during long-term storage, take the time to orient your cartridges like wine bottles, i.e. placed flat on their side. Of course, this really isn’t necessary if you burn through your ammo relatively quickly. But, if you are storing cartridges “for the long haul”, take the time to arrange them horizontally. That may require a little extra effort now, but you’ll reap the rewards down the road.

This tip courtesy Anette Wachter, www.30CalGal.com.

March 5th, 2012

by James Calhoon

(First Printed in Varmint Hunter Magazine, October, 1995)

In the course of talking to many shooters, it has become clear to me that the manufacturers of primers have done a less than adequate job of educating reloaders on the application of their primers. Everybody seems to realize that some primers are “hotter” than others and some seem to shoot better for them than others, but few reloaders know that primers have different pressure tolerances.

Primer Pressure Tolerance

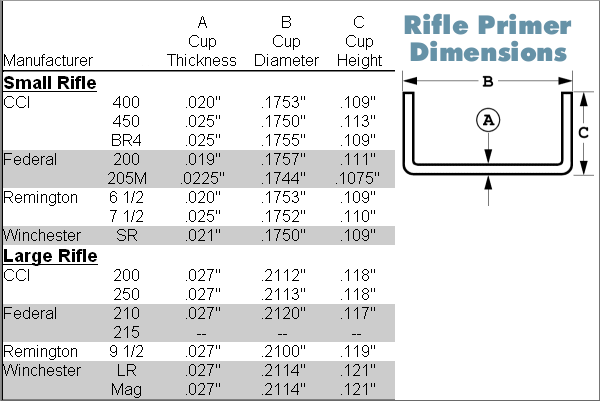

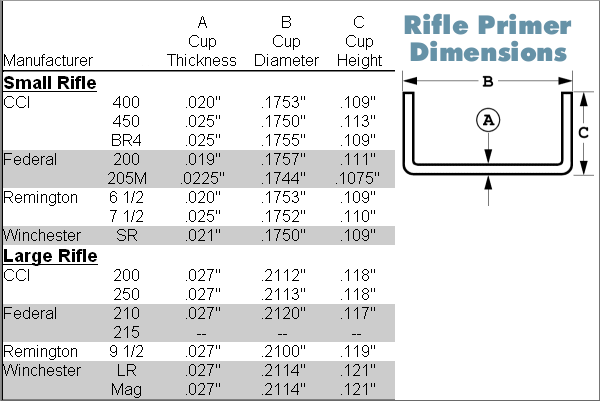

When loading a .223 to the maximum, I was getting primer piercing before I reached case overloading. I don’t know what prompted me to try CCI 450s instead of the 400s which I had been using, but I did. Presto! No more piercing! Interesting!? A primer that has a hotter ignition and yet withstands more pressure! Thats when I decided that it was time to do a dissection of all primers concerned. The chart below shows my results.

By studying the numbers (Cup “A” thickness), one can see which primers in the small rifle sections should be more resistant to primer cratering and/or piercing. Primer cup diameters are all similar and appear to follow a specification, but check out the cup thickness in the small rifle primers (Dimension “A”). Some cups are quite a bit thicker than others: .025″ for CCI 450 vs. .0019″ for Fed 200. Large rifle primers all appear to have the same cup thickness, no matter what the type. (As a note of interest, small pistol primers are .017″ thick and large pistol primers are .020″ thick.)

If you are shooting a 22 Cooper, Hornet, or a Bee, the .020″ cup will perform admirably. But try using the .020″ cup in a 17 Remington and you will pierce primers, even with moderate loads.

Considering that cup thickness varies in the small rifle primers, it is obvious that primer “flatness” cannot solely be used as a pressure indicator.

Another factor which determines the strength of a primer cup is the work-hardened state of the metal used to make the primer cup. Most primers are made with cartridge brass (70% copper, 30% zinc), which can vary from 46,000 psi, soft, to 76,000 psi tensile strength when fully hardened. Note that manufacturers specify the hardness of metal desired, so some cups are definitely “harder” that others.

What does all this mean to the reloader?

- Cases that utilize small rifle primers and operate at moderate pressures (40,000 psi) can use CCI 400, Federal 200, Rem 6 1/2, or Win SR. Such cases include 22 CCM, 22 Hornet and the 218 Bee. Other cases that use the small rifle primer can use the above primers only if moderate loads are used. Keep to the lower end of reloading recommendations.

– Cases that utilize small rifle primers and operate at higher pressures (55,000 psi) should use CCI 450, CCI BR4, Fed 205 and Rem 7 1/2.

– All the large rifle primers measured have the same thickness. Therefore choose based on other factors, such as accuracy, low ES/SD, cost, cup hardness, and uniformity.

Hope this clears up some primer confusion. If you want more information about primers, priming compounds, or even how to make primers, the NRA sells an excellent book called “Ammunition Making” by George Frost. This book tells it like it is in the ammo making industry.

April 25th, 2011

Selection from BARNES BULLETS’ Tips, Tools, and Techniques

by Ty Herring, Barnes Consumer Service

The purpose of this month’s Tip from Barnes is to make you aware of valid pressure signs in most centerfire rifle cartridges so you can keep yourself out of hot water. Following the Barnes Manual should do exactly that. Below are photos of cartridges that definitely had too much pressure. Fortunately [they] were fired in controlled circumstances and no one was injured. But this shows what can happen if you are not careful….

High-Tech Pressure Testing Equipment High-Tech Pressure Testing Equipment

At Barnes Bullets, we use some of the best equipment when we develop load data for you. Ours is state-of-the-art with a specialized “conformal” pressure system. This set-up uses a high-tech SAAMI-spec pressure barrel with a hole bored into the chamber area and a piezoelectric transducer is installed. As the pressure peaks under firing, the gauge that is specially calibrated reads the pressure and sends a signal to the control box where a technician can see the results.

For many years hand loaders have used the old fashioned trial and error method, hoping that by adding another grain of powder you don’t blow yourself up. Certain “guidelines” have been the standard — such as when the primer gets flat, or when the bolt locks up — you should stop and reduce the charge. These methods have worked for many, but some of them are more myth than reality. I’d like to go over some of these common pressure signs to help you avoid the pitfalls.

Pressure Signs That May Be Unreliable or Deceptive

When I first started hand loading centerfire rifle cartridges, I was told that when the primer flattens I should back the load down. This is one of those semi-myths. Some primers will flatten under high pressure and others will not. I’ve had some Remington primers that have blown right out of the case without ever showing any sign of flattening and on the other hand I’ve had Winchester primers that flatten with only a starting charge. I believe this to be a function of the thickness and hardness of the primer cup. The other myth that seems common is primer “cratering”. Cratering of the primer can be caused by a hot load. But it can also be a result of a slightly large firing pin hole in the bolt or a firing pin that is a bit too long or excessive headspace. Split or cracked cases are another area where it’s assumed that high pressure is the cause. Again this is only myth. Although it can be a result of high pressure — split or cracked cases are more likely caused due to a flaw in the case, improper head space or just simply from being sized and fired repetitively.

[Editor’s Note: Flattened Primers, Primer Cratering, and Cracked Cases CAN DEFINITELY BE CAUSED by excessive pressure. Accordingly, you SHOULD be careful when you see any of these conditions. If you see very flat primers or deep cratering be alerted that you may have exceeded safe pressures. Ty Herring simply makes the point that these telltale pressure signs may sometimes occur even when pressure levels are “normal” or moderate — due to the presence of other problems. Hence these indicators may be misleading. Nonetheless — all these signs (flattened primers, cratered primers, split cases) CAN be valid warnings. If you see these conditions, exercise caution because you may, in fact, have excessively hot loads.]

Valid Pressure Signs You Should Understand

So what are valid pressure signs? I’d say the most common and repeatable pressure sign that one can visually see is the “ejector groove mark”. It shows itself on the bottom of the case [between the edge of the rim and] the primer. It is caused when the pressures within the chamber force the case against the bolt face. On most bolt faces there is a round spring loaded ejector pin. On others there is a rectangular groove to eject the spent round. Under very high pressure the brass case will flow into this groove thereby causing the “ejector groove mark”. If and when you see this mark, it is a sure sign of high pressure. Some of the new high pressure cartridges such as the WSMs are made to run at these higher pressures and some factory loads will manifest the ejector groove mark even though they are within their pressure specification.

Older-Generation Cartridges

Some cartridges have very low maximum pressure ratings such as the 45-70, 30-30, 416 Rigby along with many others that will never show an ejector groove mark. Or should I say, they should never show one. By the time you reach that high of pressure in one of these rifles, it is likely the gun will be in pieces and the bolt may become part of you.

Sticky Bolt Lift and Difficult Extraction

Another common and very real high pressure sign is heavy or sticky bolt lift or extraction. This is caused due to the brass flowing and swelling in the chamber under tremendous pressure. However heavy bolt lift is not always a sign of high pressure. It may be caused by a variety of other issues. Knowing your gun and how it usually extracts a cartridge will be a clue as to whether or not you are actually getting high pressure.

This article appears courtesy Barnes Bullets. The article originally appear in the June 2011 Barnes Bullet-N Newsletter. Story tip from Edlongrange.

August 1st, 2008

With the relentless pursuit of more velocity and the “next higher node” by many reloaders, it is important to pause and think about safety. And one has to remember that most brass will not hold up to high pressure the way Lapua or RWS does. Many readers have asked us: “How does one detect excess pressure?”. Well first, one can obviously monitor the primer pockets and measure the diameter of the case near the web. Excessive stretch or pocket loosening is a sure sign you’re running too hot. There are also many visible signs of over-pressure which you can see. Reader ScottyS provided this comparison photo of cases, showing the tell-tale signs of over-pressure.

Scotty tells us: “These samples were from a lot of Federal soft-point hunting ammunition that were fired in a custom .308 with a chamber on the tight side (although still allowing a .308 Winchester GO gauge). Among the pressure symptoms were heavy recoil, sticky bolt lift, and the left case had to be manually removed from the boltface. This demonstrates why: 1) you should never assume that all lots of factory ammo are the same (and safe); and 2) you should ALWAYS wear eye protection. This also shows how high pressure can spike once you approach maximum load levels.”

Scotty noted that there was a big pressure difference between the left case and the right case, although both were fired sequentially, and both were from the same lot of ammo. So take heed–always take precautions when testing new ammo, even if it is factory-loaded.

|

To learn more about how ambient temperature (and primer choice) affect pressures (and hence velocities) you should read the article

To learn more about how ambient temperature (and primer choice) affect pressures (and hence velocities) you should read the article

CUP Pressure Measurement

CUP Pressure Measurement

It’s pretty complicated — this subject of dealing with pressure. I’m a precision shooter and have learned to excel in that discipline. You’ve got to learn to shoot the desired scores at home and in training. And once you’re capable of shooting the scores, you may not shoot the same way in the match because of the match pressure. As a result, it takes 3-4 years to learn how to shoot, and another 3-4 years to learn how to win — to deal with the match pressure. It takes several more years to learn how to do it when it counts.

It’s pretty complicated — this subject of dealing with pressure. I’m a precision shooter and have learned to excel in that discipline. You’ve got to learn to shoot the desired scores at home and in training. And once you’re capable of shooting the scores, you may not shoot the same way in the match because of the match pressure. As a result, it takes 3-4 years to learn how to shoot, and another 3-4 years to learn how to win — to deal with the match pressure. It takes several more years to learn how to do it when it counts.

High-Tech Pressure Testing Equipment

High-Tech Pressure Testing Equipment